Basketball Free Throws.

This article came from www.basketballprospectus.com and it was discussed at IBN Forums. This is all about free throw percentage. As per article says, the European players are better free throw shooters than the American players. Check out the whole article and analyze everything.

I think about basketball a lot. An unhealthy amount, really. Yet one topic I'd never given much consideration was the issue of free throw shooting. That changed during the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, when Malcolm Gladwell made the topic of foul shooting in the NBA an issue as moderator of a marquee panel. If he was a Martian, Gladwell declared, he would not understand why the world's best basketball players are not better at shooting free throws.

This led to a variety of theories and explanations throughout the day, but for a conference devoted to the numbers, what was notably absent was the data. In preparation for this column, I've crunched it by the ream in order to try to answer a handful of questions.

Is Free Throw Shooting Improving?

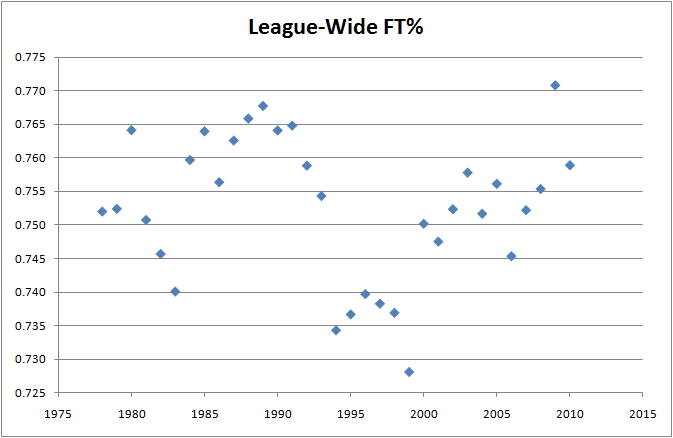

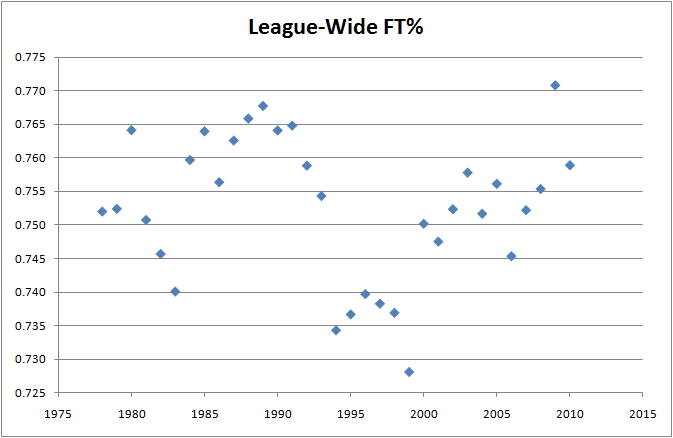

If NBA players wanted to shut Gladwell the Martian up, they would note that we are just two seasons removed from the league setting an all-time record for free throw percentage (.771). That season, however, was something of a fluke. Other than it, free throw shooting has fluctuated back and forth for the entirety of the post-merger period:

League-wide free throw shooting first reached the 75 percent range in the late 1950s, and the period where it dipped again seems to be connected almost entirely to Wilt Chamberlain's poor accuracy. Since Chamberlain slowed down and retired, free throw shooting hasn't really budged. Is that a sign that the level of play in the league is no better than it was five decades ago? Probably not. Instead, it likely reflects the point at which free throw shooting collectively stops determining NBA talent. To get the average any higher, teams would have to pass up players that are otherwise far more skilled.

What's interesting is that this is also the case at the NCAA level. As John Gasaway noted before the start of the NCAA Tournament, free throw shooting has held steady at about 69 percent in college. So both the NBA and NCAA seem to be at a free throw shooting equilibrium, but the NBA's percentage as a league is much better than the NCAA's.

Do European Players Shoot Free Throws Better?

One specific allegation I recall from Gladwell during the panel was that Europeans were doing a better job of producing good free throw shooters. While I can't find the specific quote because the Gladwell panel is not yet available online, I watched the Basketball Analytics panel and there was a reference there to shooting percentages being higher in the Euroleague.

Is this true? Instead of comparing play across the ocean, I decided to work instead with the free throw shooting of players in the NBA based on where they learned the game. As it turns out, a simple analysis shows American free throw superiority.

Looking at the African cohort reveals an issue with this method. With the exception of Christian Eyenga and perhaps Luc Richard Mbah a Moute, the other Africans in the NBA are all big men. We would expect them to be weaker as free throw shooters. To account for this, I ran a regression between height and free throw percentage for everyone with at least 100 free throw attempts this season. For each inch taller, players tend to shoot 1.2 percent worse from the line. While this doesn't totally explain the poor shooting of the African group, it does tend to even things up and puts the internationals ever so slightly ahead:

Does Height Hamper Free Throw Shooting?

As we just saw, taller players shoot worse at the line. That's not quite the same as showing that height is a hindrance to free throw shooting, however. As was noted at Sloan, part of the reason big men tend to be worse as shooters is that the smaller pool of extremely tall players and limited need for them to shoot well allows teams to tolerate a lack of skill they would not accept at other positions. At the same time, big men face certain disadvantages at the line. Their long arms and bigger hands make it difficult to shoot the ball accurately. Is there any way to distinguish between these two effects? I think there is, and it involves a novel point of reference: women's basketball.

In the WNBA, the same tradeoff between size and skill exists as in the NBA. The difference is that on the level of sheer size, the tallest female players are about the same size as NBA shooting guards. The WNBA basketball is a bit smaller, so players with bigger hands are at a slight disadvantage from that standpoint, but if size itself was the dominant factor in poor free throw shooting among big men, we would not expect to see the same kind of relationship in the women's game.

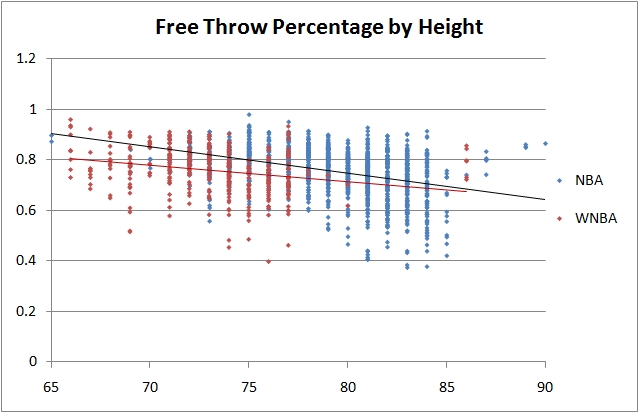

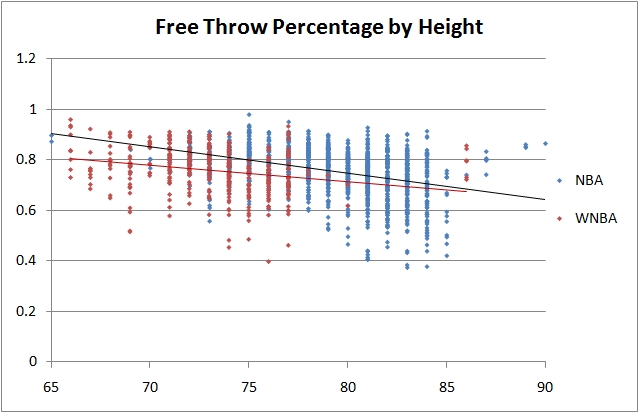

As it turns out, the results are somewhere in between. The following graph shows free throw shooting by height in the NBA (over the last five seasons, plus this year, minimum 100 attempts) and the WNBA (all the way back to 1997, again minimum 100 attempts):

The best-fit regression line for the WNBA has a slope closer to zero than the same line for the NBA, which indicates height is less of a negative factor in free throw shooting for female players. WNBA players who stand 6'5"--essentially the equivalent of the 7-foot mark in the NBA--have been highly effective at the line, shooting an average of 73.7 percent. That's better than 6'9" men. (Strangely, 6'3" and 6'4" women have not been nearly so effective.) Still, free throw percentage does tend to decrease with height even in the WNBA, suggesting there is a tradeoff of skills in addition to size hampering free throw shooting. It looks like both schools of thought have validity.

One oddity is common to both leagues: Super-tall players often tend to be accurate free throw shooters. Yao Ming, the tallest NBA player in this sample, is a career 83.3 percent shooter from the line. At 7'2", former Polish center Margo Dydek dwarfed the rest of her WNBA peers. An NBA player of equivalent height would be somewhere in the neighborhood of 7'9". Yet Dydek made 79.1 percent of her free throws during an 11-year career.

By the way, in case you were curious, WNBA players outshoot their NBA peers overall. They've made 77.5 percent of their free throws as a league three of the last four years, which would be an NBA record for accuracy.

Can Players Improve Their Free Throw Shooting?

To me, this is by far the most important of these questions. It also happens to be the most difficult to answer with any sort of certainty from the data.

First, it's worth noting that there is a slight aging curve to free throw percentage. Players tend to improve by about 0.7 percent per season up through age 27 or so. The peak for free throw percentage is an extended one, as players don't really drop off consistently until age 32. Even then, the decline phase for free throw shooting is gradual. The other skills tend to give out long before free throw shooting, as illustrated by Bob Cousy's shooting in the movie Blue Chips.

Of course, when people talk about players improving their free throw shooting, that's not really what they mean. They're wondering instead why notoriously poor shooters like Dwight Howard and Shaquille O'Neal are unable to get in the gym and practice to improve their accuracy at the line. Consider me skeptical that such development is really possible for most players. Flipping around the perspective, most NBA players spend hours per week honing their shot at the line. Yet nearly all of them continue to shoot more or less the same percentage. It is possible that, beyond a certain point, additional practice simply no longer has any benefit.

To answer the question of whether practice helps at the line, I looked for pairs of seasons where the same player shot at least 100 free throws both years, then used statistics to evaluate how often the change in their percentage was larger than would be expected from random chance alone. As it turns out, players do seem intrinsically different at the line on a fairly regular basis--but this is true in both directions.

We would expect, based on the normal distribution, that 2.5 percent of players would either improve or decline by at least two standard deviations from one year to the next. In fact, nearly three times as many players made such a big jump (7.2 percent). But more than twice as many (5.5 percent) saw their shooting decay at the line. Free throw shooting, for whatever reason, is more random than chance would suggest.

There are more players taking sizeable leaps forward than backward, which suggests that practice is paying off for some players. However, the difference between the two groups is relatively small. We're talking about 90 players over the last three decades--about three per year. This is not something that is happening on a routine basis.

On the plus side, the players who made these improvements did tend to maintain them. The average player who improved by a statistically significant amount went from shooting 68.7 percent to 78.7 percent (precisely a 10-percent improvement) and shot 76.0 percent in year three.

A couple of superstar power forwards serve as the poster children for improving at the line. Chris Webber made the second-biggest leap in standardized terms, going from 45.4 percent during the lockout-shortened 1998-99 season (when free throw shooting was down around the league) to 75.1 percent in 1999-00. Webber had never previously made more than 60 percent of his free throws, but he only dropped below 70 percent once during the next seven seasons.

Karl Malone actually shows up on the list of most improved shooters in consecutive years. He went from making 48.1 percent of his free throws as a rookie to 70.0 percent in year three and only dipped below 70 once thereafter in his 19-year career, which he finished as the league's all-time leader in free throws.

The experience of Webber and Malone should serve to inspire players working tirelessly in the gym. At the same time, a handful of examples do not set reasonable expectations. In general, history tells us that players are who they are at the free throw line, which is worth remembering the next time you complain about missed free throws.

This free article is an example of the kind of content available to Basketball Prospectus Premium subscribers. See our Premium page for more details and to subscribe.

Kevin Pelton is an author of Basketball Prospectus. You can contact Kevin by clicking here or click here to see Kevin's other articles.

| March 30, 2011 Free Throws Truth and Rumors by Kevin Pelton | | |

| |

I think about basketball a lot. An unhealthy amount, really. Yet one topic I'd never given much consideration was the issue of free throw shooting. That changed during the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, when Malcolm Gladwell made the topic of foul shooting in the NBA an issue as moderator of a marquee panel. If he was a Martian, Gladwell declared, he would not understand why the world's best basketball players are not better at shooting free throws.

This led to a variety of theories and explanations throughout the day, but for a conference devoted to the numbers, what was notably absent was the data. In preparation for this column, I've crunched it by the ream in order to try to answer a handful of questions.

Is Free Throw Shooting Improving?

If NBA players wanted to shut Gladwell the Martian up, they would note that we are just two seasons removed from the league setting an all-time record for free throw percentage (.771). That season, however, was something of a fluke. Other than it, free throw shooting has fluctuated back and forth for the entirety of the post-merger period:

League-wide free throw shooting first reached the 75 percent range in the late 1950s, and the period where it dipped again seems to be connected almost entirely to Wilt Chamberlain's poor accuracy. Since Chamberlain slowed down and retired, free throw shooting hasn't really budged. Is that a sign that the level of play in the league is no better than it was five decades ago? Probably not. Instead, it likely reflects the point at which free throw shooting collectively stops determining NBA talent. To get the average any higher, teams would have to pass up players that are otherwise far more skilled.

What's interesting is that this is also the case at the NCAA level. As John Gasaway noted before the start of the NCAA Tournament, free throw shooting has held steady at about 69 percent in college. So both the NBA and NCAA seem to be at a free throw shooting equilibrium, but the NBA's percentage as a league is much better than the NCAA's.

Do European Players Shoot Free Throws Better?

One specific allegation I recall from Gladwell during the panel was that Europeans were doing a better job of producing good free throw shooters. While I can't find the specific quote because the Gladwell panel is not yet available online, I watched the Basketball Analytics panel and there was a reference there to shooting percentages being higher in the Euroleague.

Is this true? Instead of comparing play across the ocean, I decided to work instead with the free throw shooting of players in the NBA based on where they learned the game. As it turns out, a simple analysis shows American free throw superiority.

Region # FT%

------------------------

Africa 7 .696

Americas 14 .769

Asia 2 .720

Australia 4 .507

Canada 5 .804

Europe 49 .766

Middle East 1 .600

------------------------

Foreign 82 .757

Domestic 364 .765While Europeans are ever so slightly higher, American-reared NBA players outshoot their foreign peers by 0.8 percent at the free throw line. This doesn't seem to just be a fluke. I had Neil Paine of Basketball-Reference.com run long-term numbers for me, and American players were slightly better over the last decade, .757 to .755.Looking at the African cohort reveals an issue with this method. With the exception of Christian Eyenga and perhaps Luc Richard Mbah a Moute, the other Africans in the NBA are all big men. We would expect them to be weaker as free throw shooters. To account for this, I ran a regression between height and free throw percentage for everyone with at least 100 free throw attempts this season. For each inch taller, players tend to shoot 1.2 percent worse from the line. While this doesn't totally explain the poor shooting of the African group, it does tend to even things up and puts the internationals ever so slightly ahead:

Region # FT% xFT% Diff

---------------------------------------

Africa 7 .696 .735 -.039

Americas 14 .769 .755 .014

Asia 2 .720 .688 .032

Australia 4 .507 .727 -.219

Canada 5 .804 .777 .027

Europe 49 .766 .733 .033

Middle East 1 .600 .600 .000

----------------------------------------

Foreign 82 .757 .740 .017

Domestic 364 .765 .767 -.002Europeans do in fact score especially well by this measure. Because most Europeans in the NBA are post players, we'd expect them to struggle at the line more than they do. Individually, four of the eight players who most outshoot their height are European (Andrea Bargnani, Pau Gasol, Danilo Gallinari and Dirk Nowitzki). European guards don't appear to be any better as a group than their American peers, but perhaps we can learn something in terms of producing big men with soft touch from the perimeter and the line.Does Height Hamper Free Throw Shooting?

As we just saw, taller players shoot worse at the line. That's not quite the same as showing that height is a hindrance to free throw shooting, however. As was noted at Sloan, part of the reason big men tend to be worse as shooters is that the smaller pool of extremely tall players and limited need for them to shoot well allows teams to tolerate a lack of skill they would not accept at other positions. At the same time, big men face certain disadvantages at the line. Their long arms and bigger hands make it difficult to shoot the ball accurately. Is there any way to distinguish between these two effects? I think there is, and it involves a novel point of reference: women's basketball.

In the WNBA, the same tradeoff between size and skill exists as in the NBA. The difference is that on the level of sheer size, the tallest female players are about the same size as NBA shooting guards. The WNBA basketball is a bit smaller, so players with bigger hands are at a slight disadvantage from that standpoint, but if size itself was the dominant factor in poor free throw shooting among big men, we would not expect to see the same kind of relationship in the women's game.

As it turns out, the results are somewhere in between. The following graph shows free throw shooting by height in the NBA (over the last five seasons, plus this year, minimum 100 attempts) and the WNBA (all the way back to 1997, again minimum 100 attempts):

The best-fit regression line for the WNBA has a slope closer to zero than the same line for the NBA, which indicates height is less of a negative factor in free throw shooting for female players. WNBA players who stand 6'5"--essentially the equivalent of the 7-foot mark in the NBA--have been highly effective at the line, shooting an average of 73.7 percent. That's better than 6'9" men. (Strangely, 6'3" and 6'4" women have not been nearly so effective.) Still, free throw percentage does tend to decrease with height even in the WNBA, suggesting there is a tradeoff of skills in addition to size hampering free throw shooting. It looks like both schools of thought have validity.

One oddity is common to both leagues: Super-tall players often tend to be accurate free throw shooters. Yao Ming, the tallest NBA player in this sample, is a career 83.3 percent shooter from the line. At 7'2", former Polish center Margo Dydek dwarfed the rest of her WNBA peers. An NBA player of equivalent height would be somewhere in the neighborhood of 7'9". Yet Dydek made 79.1 percent of her free throws during an 11-year career.

By the way, in case you were curious, WNBA players outshoot their NBA peers overall. They've made 77.5 percent of their free throws as a league three of the last four years, which would be an NBA record for accuracy.

Can Players Improve Their Free Throw Shooting?

To me, this is by far the most important of these questions. It also happens to be the most difficult to answer with any sort of certainty from the data.

First, it's worth noting that there is a slight aging curve to free throw percentage. Players tend to improve by about 0.7 percent per season up through age 27 or so. The peak for free throw percentage is an extended one, as players don't really drop off consistently until age 32. Even then, the decline phase for free throw shooting is gradual. The other skills tend to give out long before free throw shooting, as illustrated by Bob Cousy's shooting in the movie Blue Chips.

Of course, when people talk about players improving their free throw shooting, that's not really what they mean. They're wondering instead why notoriously poor shooters like Dwight Howard and Shaquille O'Neal are unable to get in the gym and practice to improve their accuracy at the line. Consider me skeptical that such development is really possible for most players. Flipping around the perspective, most NBA players spend hours per week honing their shot at the line. Yet nearly all of them continue to shoot more or less the same percentage. It is possible that, beyond a certain point, additional practice simply no longer has any benefit.

To answer the question of whether practice helps at the line, I looked for pairs of seasons where the same player shot at least 100 free throws both years, then used statistics to evaluate how often the change in their percentage was larger than would be expected from random chance alone. As it turns out, players do seem intrinsically different at the line on a fairly regular basis--but this is true in both directions.

We would expect, based on the normal distribution, that 2.5 percent of players would either improve or decline by at least two standard deviations from one year to the next. In fact, nearly three times as many players made such a big jump (7.2 percent). But more than twice as many (5.5 percent) saw their shooting decay at the line. Free throw shooting, for whatever reason, is more random than chance would suggest.

There are more players taking sizeable leaps forward than backward, which suggests that practice is paying off for some players. However, the difference between the two groups is relatively small. We're talking about 90 players over the last three decades--about three per year. This is not something that is happening on a routine basis.

On the plus side, the players who made these improvements did tend to maintain them. The average player who improved by a statistically significant amount went from shooting 68.7 percent to 78.7 percent (precisely a 10-percent improvement) and shot 76.0 percent in year three.

A couple of superstar power forwards serve as the poster children for improving at the line. Chris Webber made the second-biggest leap in standardized terms, going from 45.4 percent during the lockout-shortened 1998-99 season (when free throw shooting was down around the league) to 75.1 percent in 1999-00. Webber had never previously made more than 60 percent of his free throws, but he only dropped below 70 percent once during the next seven seasons.

Karl Malone actually shows up on the list of most improved shooters in consecutive years. He went from making 48.1 percent of his free throws as a rookie to 70.0 percent in year three and only dipped below 70 once thereafter in his 19-year career, which he finished as the league's all-time leader in free throws.

The experience of Webber and Malone should serve to inspire players working tirelessly in the gym. At the same time, a handful of examples do not set reasonable expectations. In general, history tells us that players are who they are at the free throw line, which is worth remembering the next time you complain about missed free throws.

This free article is an example of the kind of content available to Basketball Prospectus Premium subscribers. See our Premium page for more details and to subscribe.

Kevin Pelton is an author of Basketball Prospectus. You can contact Kevin by clicking here or click here to see Kevin's other articles.

Comments

Post a Comment